Case study of the touch response

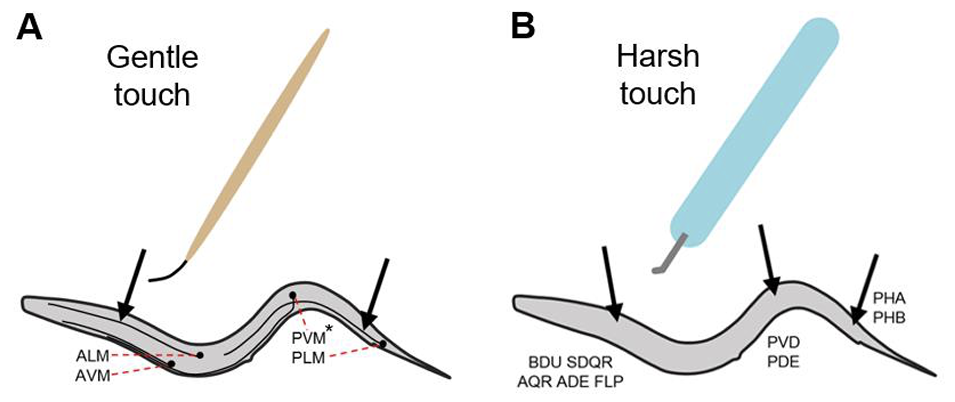

In this post, we link neural stimulation with feedback to examine mechanical touch induced locomotion responses. C. elegans responds to both gentle and harsh mechanical touches to its body via activating escape responses. If the touch is around anterior body region, it responds with backward locomotion whereas for posterior touch, it responds with forward locomotion. Theese responses are mediated by a group of sensory neurons distributed in both posterior and anterior body regions as shown below.

(image credit: Automated Analysis Of Experience-Dependent Sensory Response Behavior In Caenorhabditis Elegans, U of Pennsylvania)

(image credit: Automated Analysis Of Experience-Dependent Sensory Response Behavior In Caenorhabditis Elegans, U of Pennsylvania)

Here we validate movements that the baseline model generates for gentle and harsh anterior/posterior touch and examine scenarios afterwards the effect of in-silico ablation on them. For gentle anterior/posterior touch, we stimulate ALM,AVM and PLM respectively. For harsh anterior/posterior touch, we stimulate FLP, ADE, BDU, SDQR and PVD, PDE respectively.

(Left: Gentle Anterior Touch, Middle: Harsh Anterior Touch, Right: Harsh Posterior Touch)

As shown above, the simulated body movements for gentle anterior and harsh posterior/anterior touch responses indeed produce typical directional movement patterns. i.e., forward; during posterior touch neural stimulation and (ii) backward; during anterior touch stimulation (we will get to the gentle posterior touch in a moment). We therefore proceed to explore how these movements are affected by either random or targeted in-silico neuron ablations.

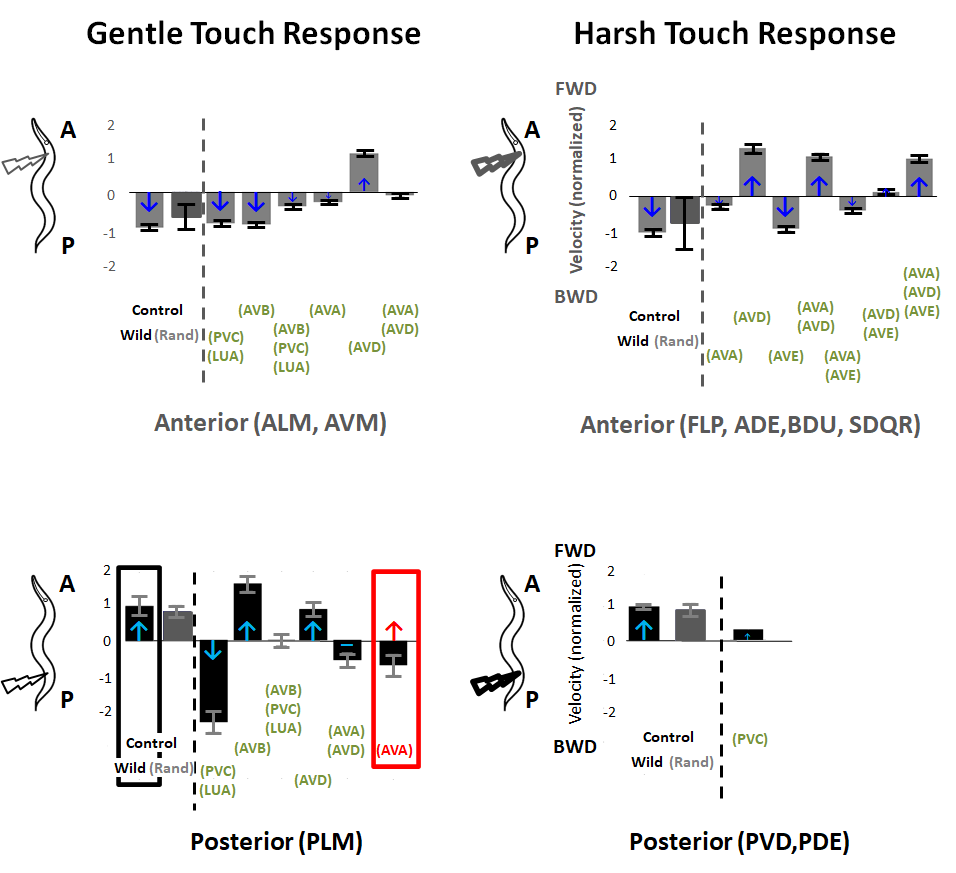

The above figure shows the velocity of each locomotion response after in-silico ablation. Each velocity is normalized in respect to the velocity of the control scenario (i.e., no ablation). When we perform in-silico ablation of random pair of neurons (denoted Rand) we see that the ablation does not change, on average, the characteristic velocities of the four touch responses that we considered. This is indeed expected since the locomotions are mediated by neural circuits consisting particular set of neurons.

Next, we consider targeted in-silico ablations as done in the in-vivo experiments and compared velocities and directions of movements with descriptions published in earlier experiments, where arrows indicate in-vivo reported data; color of arrows indicates consistency (blue); or disparity (red)). Remarkably, we observe that the results are qualitatively consistent with previous in-vivo findings!

For PLM stimulation (Gentle Posterior), in-silico ablations provided novel predictions. In particular, while multiple ablations are consistent with in-vivo, the model indicates that ablation of either (AVA)+(AVD) or (AVA) significantly alter the response such that the movement is slower than control and in about half of the simulated cases invokes backward movement instead of the control forward movement. Since ablation of (AVD) alone does not result with significant change in the response, the model identifies AVA presence to have vital role in forward movement and contradicts the classical classification of AVA as a ‘backward’ command neuron and the reported results in experiment.

(Left: Posterior Gentle Touch with no ablation (Model), Right: (Experiment))

We validated the model prediction with a novel in-vivo experiment. In particular, we used optogenetic miniSOG method to ablate AVA neurons in ZM7198 mutants and compared their responses to gentle posterior touch with control wild type N2 animals. Gentle posterior touch was performed mechanically with a hair touching the posterior part of the body. As shown above, control animals exhibited sustained forward movement with average instantaneous velocity of 147±30 μm/s for the duration of at least 10s after the posterior touch onset. In-vivo control worms exhibited matching velocities, forward postures and bearing with in-silico control worms.

(Left: Posterior Gentle Touch with AVA ablation (Model), Right: (Experiment))

When we ablate AVA for in-vivo worms, we observed that they were unable to perform sustained forward movement. Behavioral assays indicated average instantaneous velocity of 19±12μm/s after the posterior touch. In addition, 61% of tested animals (16/26) performed spontaneous backward movement for the duration of at least 1s. The result is in qualitative agreement with in-silico ablation of AVA. Overall, these results show the potential of the baseline model to produce novel hypothesis that can inform experimental analyses.