Model variations for investigation of simulated behaviors

In this post we consider expandibility of the baseline model to investigate simulated behaviors. The baseline model has shown its ability to generate overall similar movements as in in-vivo experiments and to provide novel predictions. However, in depth analysis of motion shows that the characteristics of locomotion, such as eigenworm coefficients, do not precisely coincide with in-vivo values. Eigenworm coefficients are quantitative metrics describing the C. elegans posture during typical locomotion. We use this metric to evaluate the closeness of the simulated locomotion compared to in-vivo locomotion.

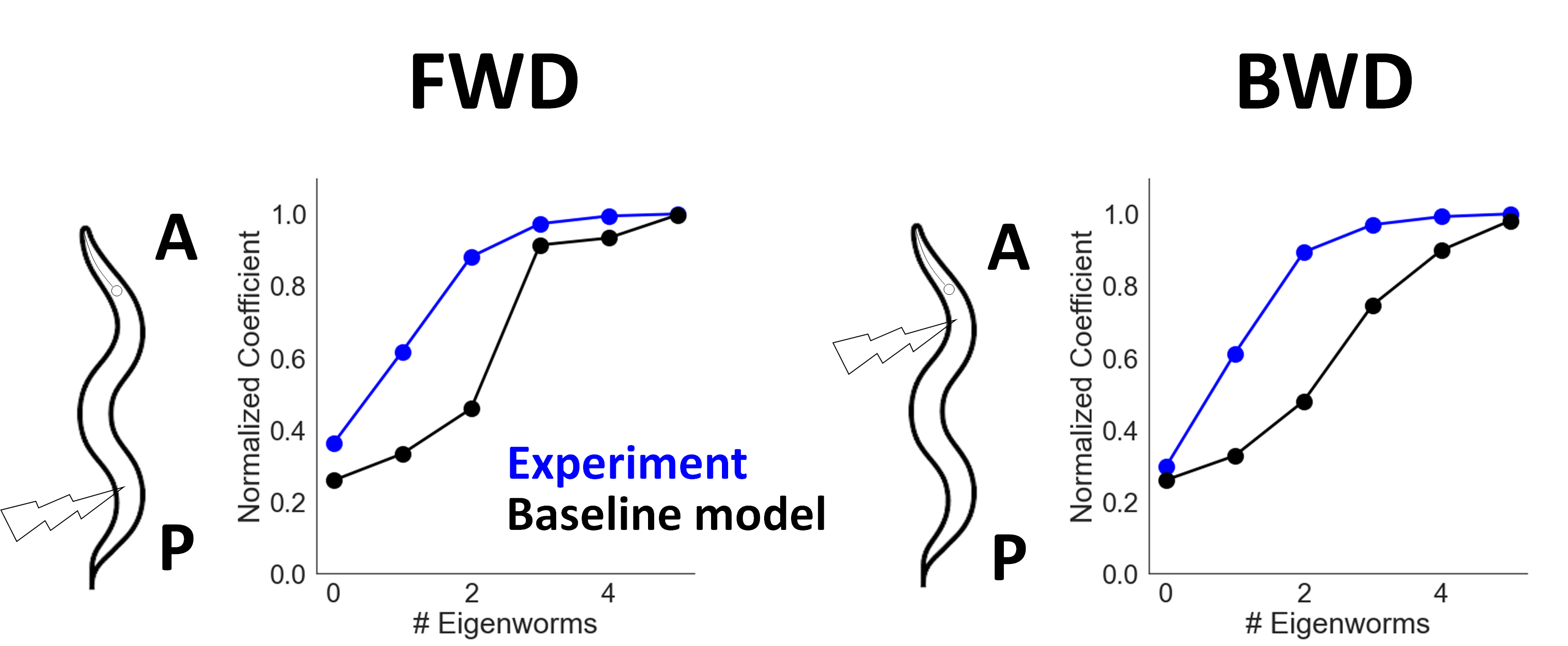

(Left: eigenworm coefficients of FWD locomotion, Right: BWD locomotion)

(Left: eigenworm coefficients of FWD locomotion, Right: BWD locomotion)

As shown above, we see that there is a gap between the model obtained coefficients (black) and experiment (blue). This is unsurprising since the baseline model, by design, includes only “baseline” layers of individual neural dynamics and connections to reflect the dominant dynamic patterns and behavior. Novel experimental data shows that there are additional “higher order” properties that play role in neural activity and behavior such as spiking neurons, extra-synaptic connections, novel connectomics data. We incorporate these additional layers to the model to investigate their effects on simulated locomotion.

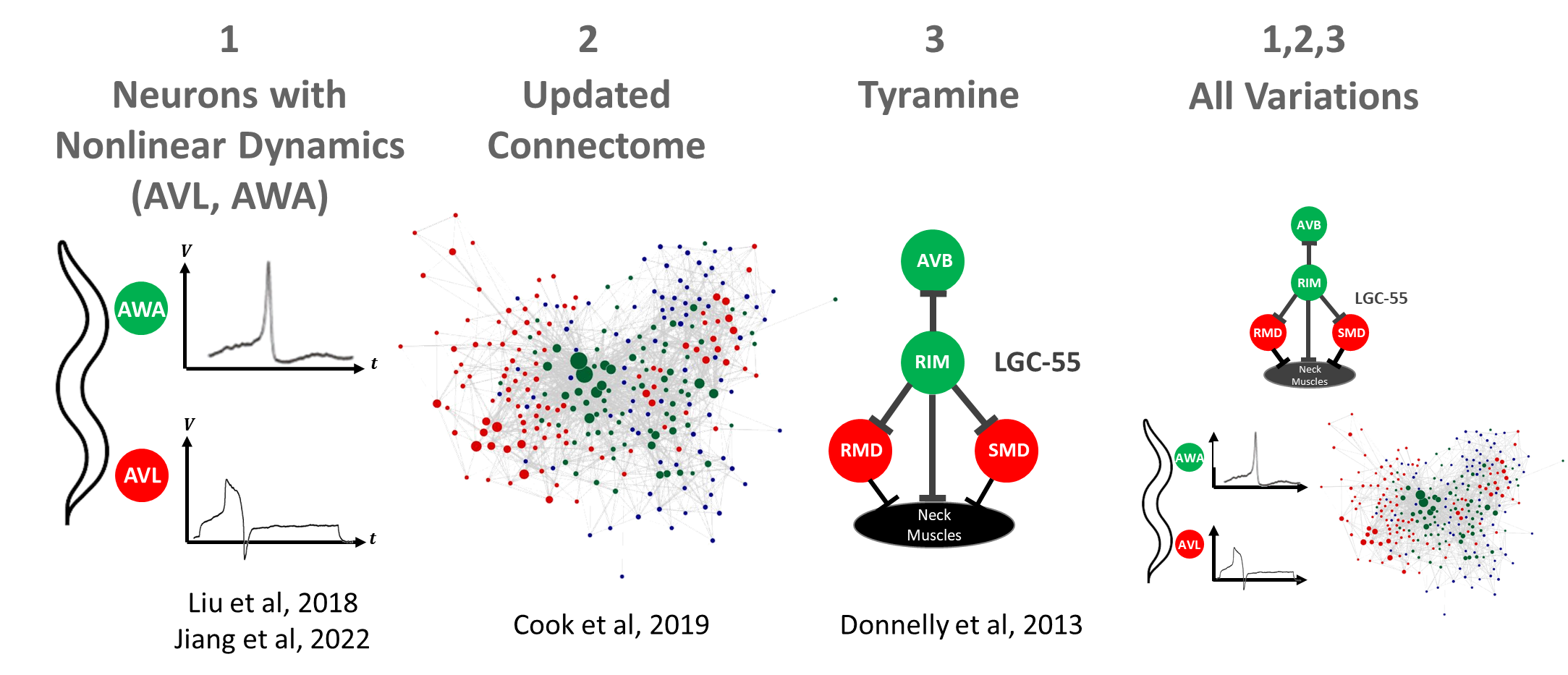

The model variations we consider are i) Tyramine gated chloride channels (LGC-55), ii) neurons with non-linear channels and iii) variation of the connectome. Each of these variations was recently proposed in experiments to have a potential role in facilitating or regulating locomotion. Adding the three variations to the baseline model can be done by either adding new interaction channels (LGC-55), or modifying the weight matrices that define the connectome, or by adding new individual neuron channels (non-linear channels). Since the model is designed to be easily configurable and expandable, such additions can be inserted or ablated from the baseline model with ease.

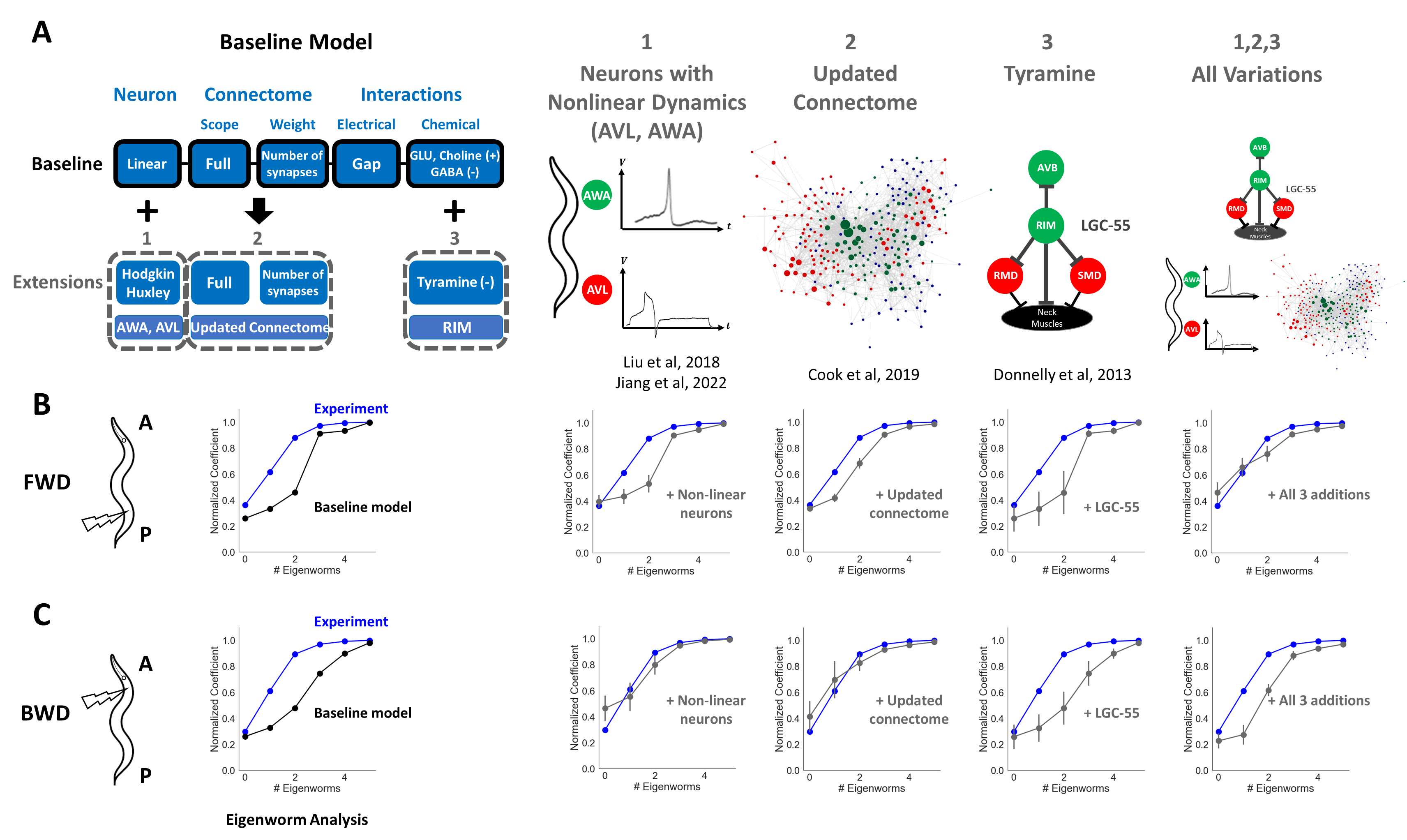

Above figure describes the comparison of in-vivo eigenworm coefficients compared with baseline model coefficients versus the model with each variation of the baseline.

For incorporation of LGC-55, variation (i), we observe that coefficients for both FWD and BWD locomotion almost do not change from the baseline values. This is indeed expected since LGC-55 was found to be primarily associated with head turning behavior during pirouette maneuver, e.g., omega turn, rather than forward locomotion.

Incorporating selected neurons’ having nonlinear channels, variation (ii), appears to have an effect on the eigenworm coefficients. However, the error between in-vivo coefficients and model variant generated coefficients is greater than the baseline model error, primarily due to the first eigenworm coefficient. We found that this effect mostly originates from incorporation of AVL since including non-linear channels in AWA alone did not have noticeable effects on the baseline coefficients.

Updating the connectome data (both gap and synaptic) to the dataset published in Cook et al, variation (iii), significantly decreased the error between the variant model and in-vivo coefficients. Especially the in-vivo coefficients were within the confidence interval (P = 99%) of model obtained coefficients for BWD locomotion, indicating a close match.

Combining all three variations further minimized the error for FWD locomotion, but slightly increased the error for BWD locomotion.

Let’s take a look at simulated behaviors after model variation. Here we show the simulated locomotion after updating connectome, the variation (iii) that resulted in most significant improvement to eigenworm coefficients, and compare to baseline locomotion.

(Top Left: FWD locomotion (baseline), Top Right: FWD locomotion (update connectome), Bottom Left: BWD locomotion (baseline), Bottom Right: BWD locomotion (update connectome))

As shown above, we can see that both FWD and BWD locomotion achieves more ‘sine-shaped’ postures, and hence makes the movement look more ‘natural’. These results show that variations of the baseline model allow to further study the effects of new biophysical data on locomotion and quantify the contribution of each to match observed in-vivo behaviors.